‘here, no fur ye' — Exhibition Review @ Generator Projects

Here, ye no fur - exhibition at Generator Projects, Dundee

Open for a few more days (through May 23rd), Edinburgh-based artist Lewis Bissett has staked his claim on Gallery 2 of Generator Projects. The irony of an exhibition exploring working class culture being held in a gallery situated within an industrial site is not lost on me as I squat to peer at the papier-mâché sculptures & found-object minutiae littering the centre of the space.

A neon mishmash of scrawls, squiggles, sculptures, luminous smiling faces and fresh Adidas kicks show that this is an exhibition that pays homage to the working class, and the artist's native Falkirk.

Chatting with Lewis outside, one thing that struck me was his ingenuity: under the flashing neon of the dingy-lit space, I didn’t even question that these were not just worn out pairs of shoes, but crafted from electrical tape.

Scattered around are half-deflated footballs atop charity shop mugs, two key symbols in the visual coda of working class aesthetics, un-appropriated and unapologetic.

A lot of these works are older, fished out of boxes during the lockdown. Others were created during the time of Covid with Bissett stating the importance of keeping his hands busy for mental health maintenance.

One work ‘F.A.B (father and boay)’ features the apprentice's shield of the artist’s father from the 1980s, with an applied relief depicting a thistle with a thought-cloud emanating from its lurid pink crown, with the word ‘BOA | ISH’

This term ‘BOAYISH' came from Bissett correcting someone who assumed his work was ‘laddish.’ His response was, ‘I’m more boyish than anything.’ These colloquial phrases embody the exhibition title ‘no fur ye’, whereby the working classes forge their own dialects and share their own private language, a feature often bastardised by elites for entertainment value. It’s a nudge and a wink, if ye ken - ye ken. And I am inclined to agree, the joy emanating from these works has the authenticity and simplicity of boyhood.

My favourite from this exhibition is a sculptural work titled ‘Argonaut’, which features a large head resting on a pile of books stacked high upon a bedside table littered with ephemera - a nod to the boy living inside the artist.

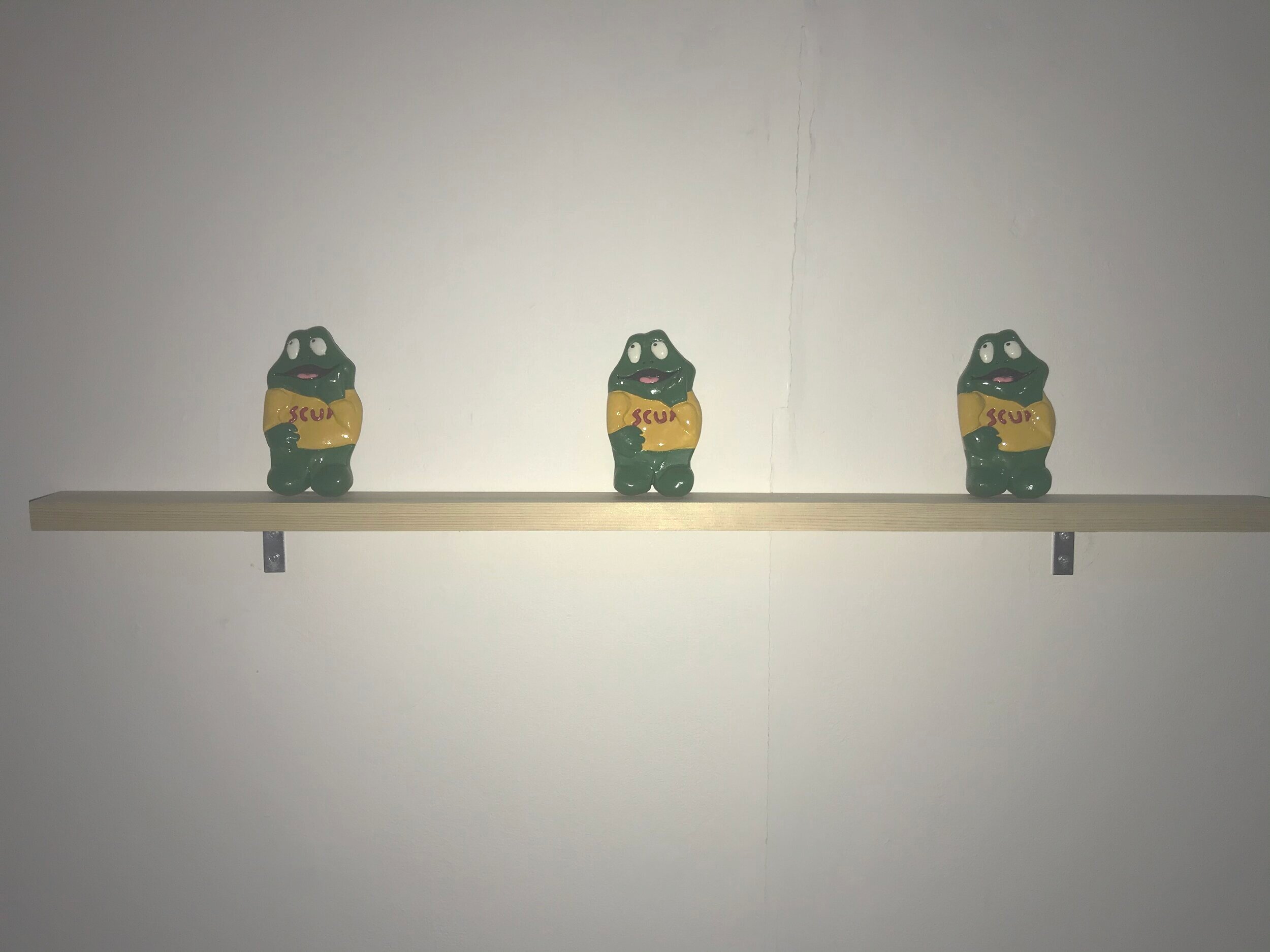

Family is clearly integral here, and the room is filled with biography, recalling the old adage: ‘he knows who he is, cause he knows where he comes from.’ Bissett states that the 3 neon floats that glow from the walls (subtitled as: Local God for a regional religion) were made by his family and himself during lockdown, out of toilet tissue, to commemorate the parades they attended.

The use of neon is a tribute to a Blackpool ride ‘Alice in Wonderland’, the artist and his family would holiday in the Disneyland of the Working Class every September Weekend. The tribute pairs well with the lurid smiling faces that abound within the space, entering the exhibition is akin to falling down the rabbit's hole.

‘Argonaut’ is not the only Greek reference to be found here. On one wall is a giant snake eating itself, an ouroboros titled ‘Eat Your Friends’, made from pulped Amazon boxes the artist rescued from student’s bins during his time as a porter for student accommodation in Edinburgh.

Bissett likens this mythology to Scotland’s relationship with Freemasonry, and its lexicon of iconography that has become emblematic of the working class men from wee toons who formed these sects.

In essence, Bissett makes the greatest revolt against classism within the arts industry, not by defending the working class but simply celebrating them. The sanctity of the proletariat is apparent within these works, the semi-secular communities that we have forged from mythology, ingenuity and creativity.

Words by Cheryl McGregor