Runes

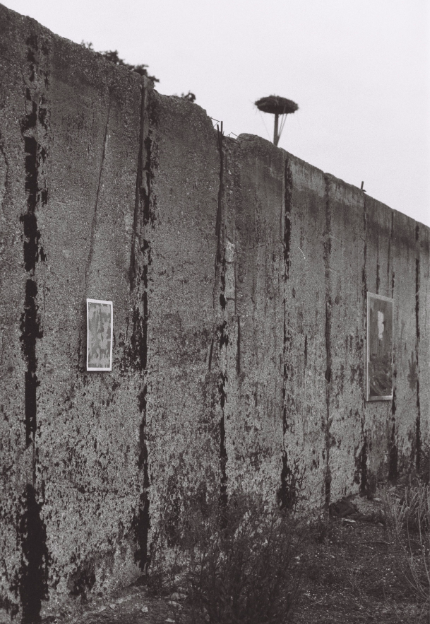

This exhibition began with a journey to Sweden in 2018; Arthur Laidlaw began by shadowing a New York Times journalist as he investigated the rise of Neo-pagans, and their use of religious symbolism as a mask for radical nationalism

On the making of Runes

Travelling through Sweden in February is starkly beautiful, yet undeniably bleak; the whiteness of the landscape felt more oppressive each day, as we confronted clear statements of xenophobia by many of our subjects. My hope is that these paintings echo the fairytale nature of my experience; a beguiling, persuasive facade, that sucks in the viewer – only to realise the true nature of the image as something horrifying, when it may already be too late.

The coronavirus has had many unexpected consequences, but also some very predictable outcomes: new anti-immigration policies and legislation by the likes of Victor Orbán in Hungary, Andrzej Duda in Poland, Sebastian Kurz in Austria, and of course Donald Trump in the USA. The virus has presented a means for governments to enact so-called “justifiable” isolationist agendas; it is dressed up as a political reflection of the personal stay at home order. Sweden is no different. Flawed policies in response to COVID-19 were driven by the country’s exceptionalism, and the disproportionate number of deaths of Swedes by Somali heritage is a further reminder of the country’s structural racism – both are the consequence of an emboldened radical nationalism within the country.

At a moment when the fight over historical symbols and their meaning is particularly fraught, these abstractions from Scandinavian landscapes ask how easily iconography can be manipulated, and what motivates its continued reappropriation for political ends.

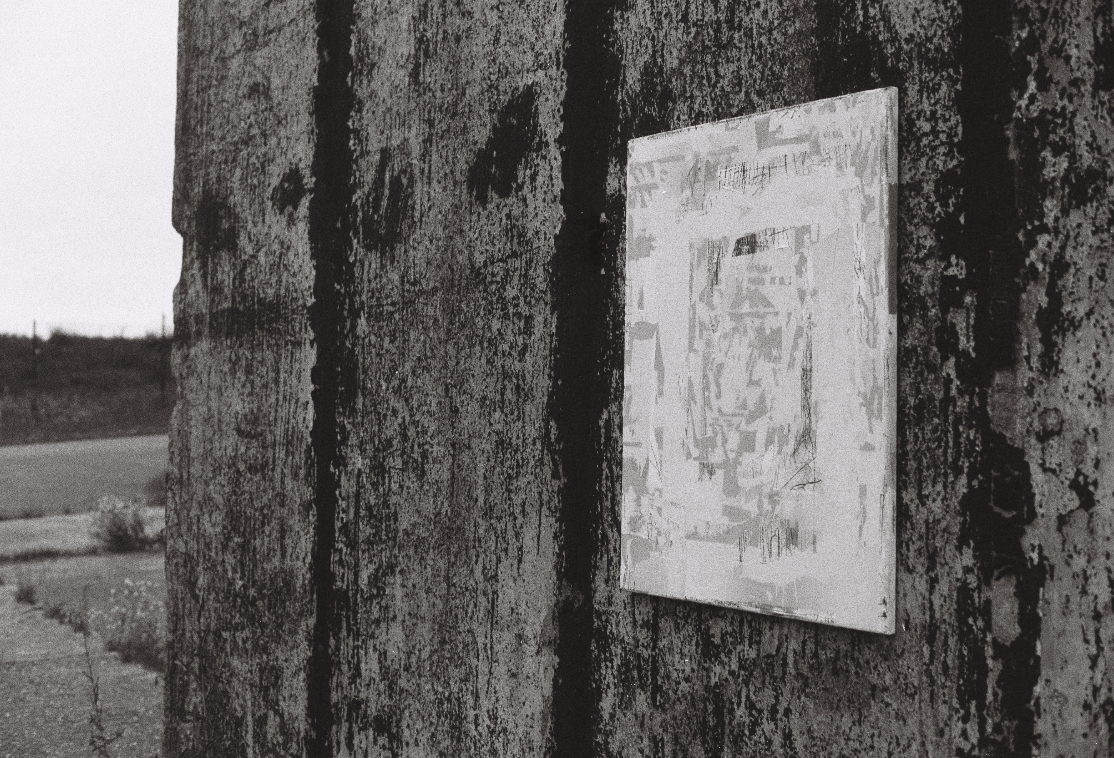

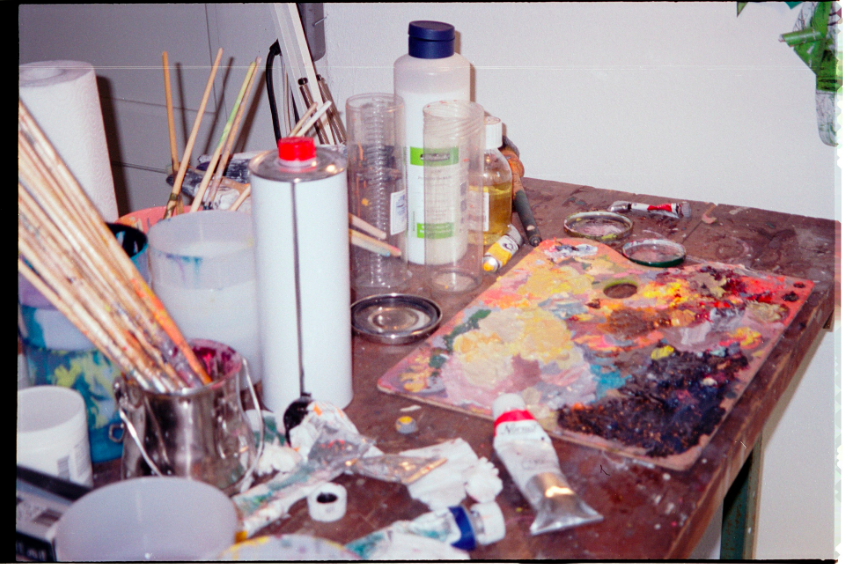

Formally, each of the works has emerged from an analogue process; 35mm and Super 8 film were used to document the landscape, while a number of in situ sketchbook drawings and notes became the basis for many of the compositions now seen in the exhibition. Runes exist, as is the case for most letters or glyphs, in the space between image and word. I wanted my works to function similarly, asking the viewer to extract figuration and symbolic meaning from geometry and abstraction, using only the contextual shapes and marks of the pantings as clues to guide them.

Viewing Room

Accompanying text by New York Times Journalist, Richard Martyn-Hemphill

(Click on artwork, to view full image in isolation)

Hotell Saga

100 x 120 cm

Looking at the cryptic scripts of runestones, I like to weigh up how an ancient Norse inscriber may have experienced the magical power of a delete button. Fantastically useful, no doubt. Then again, to wax nostalgic for a second: an absence of deletion is also what makes immediate and constant accuracy a necessity. On top of that, a patient mastery of stone delivers endurance and brevity — a literal cutting to the chase for a message crafted to last. Certainly, today’s 24-hour newscycle hacks can learn from these anonymous forebears. Yet as any journalist will tell you, brevity also brings unease: what stories, due to lack of time, resources, interest or ingenuity, have been left untold?

Hoarding

100 x 120 cm

Looking through Arthur’s latest series, “Runes,” I can see lots of hints at untold stories. His works here — as ever infused like John Ruskin’s with rocks, ruins and religion — are drawn from a long, winding, cold, frenetic, exhausting road trip we took together across Sweden two winters ago. During that trip, I was on assignment alongside the Norwegian reporter Henrik Pryser-Libell and the Dutch photographer Jasper Juinen. Our quickfire output over the next few weeks included a set of stories looking at Viking symbols, immigration, contemporary paganism and radical nationalism across Sweden. Promising to keep distance and discretion, Arthur joined the three of us in the car from Gothenburg. Then, we drove east on a winding journey to Stockholm, stopping to see various Viking sites and even witnessing a neo-pagan ritual, known as a Blót.

Throughout, Arthur proved a helpful backseat observer of the observers — questioning our questions, musing on the nature of symbols, keeping us in check.

The View From Hotell Saga (SOLD)

20 x 30 cm

The View From Hotel Saga II

20 x 30 cm

Less glowingly, Arthur’s phone was stolen in Gothenburg. Like the rune inscribers without the delete button, however, this might have actually sharpened his eye. Undeterred by the various risks of going incommunicado, he struck out on some of his own adventures, resorting to other trusted tools. His pen and sketchbook were rarely out of hand as he ventured at frosty daybreak in post-industrial towns like Borlänge, or as he snooped around the evocatively named but otherwise eerily sterile Hotell Saga.

Trudging in deep snow across the Norse burial mounds of Gamla Uppsala, Arthur even brandished a vintage Super 8 camera with precious few reels of film — just in time to capture a surreal sequence of Swedish soldiers marching past the tombs of unnamed kings.

The Road To Gamla Uppsala

30 x 40 cm

The Road To Gamla Uppsala II

30 x 40 cm

“Borlänge IV is the culmination of several different working methods, using masking tape, hand cut paper stencils, and sprayed gouache to achieve a suspended, fragmented composition. As with many of Laidlaw’s earlier works, the heavy black lines of monoprinting can be seen – though their inclusion here felt more relevant for textural reasons, rather than as outlines for the central motif.”

Rune I

29.7 x 42 cm

Gamla Uppsalla Mosque IV

30 x 40 cm

Rune II

29.7 x 42 cm

Over two years later and here we are: an online exhibition launched from a safe social distance.

Such travels in Scandinavia feel a distant memory in our new abnormal. The recurrent vision of Swedish exceptionalism — whether through Vikings or Volvos, IKEA or ABBA — is back again, this time with the country’s response to the coronavirus.

Most other nations bolted into government-enforced lockdown. Not the Swedes, though, who took a more voluntary approach that polarised international opinion, stoking fierce debates not unlike its unilateral decision to open doors to Syrian refugees five years before. Was this the cool-headed Scandinavian stereotype of public health pragmatism and sensible citizens following smart advice — or was it a needless sacrifice of human life at the altar of the economy?

Runes - assemblage of Super 8, digital video, field recordings, and works on paper & canvas, 2018-2020

Under A Blood Red Sky

29.7 x 42 cm

Sweden Underwater III

29.7 x 42 cm

“These were the first works produced in the studio for RUNES. The cyanotype process allows a complex assemblage of material layers to be rendered as a single, unified finished image. This process – the reduction of many figurative sources to a pseudo-abstract form – began a line of enquiry that was expanded upon in later works”

Sweden Underwater

29.7 x 42 cm

Those debates over Sweden’s pandemic response will rage on, as they will in other countries. But back to the various trends we spotted on that trip in Sweden — rising nationalism, identity angst.

Eclipsed as they are by the coronavirus, they are unlikely to recede at a time of hardening borders and economic storm clouds ahead. In fact, if the verdict of the historian Yuval Noah Harari is apt, then these trends could accelerate and widen with coronavirus. “That is the nature of emergencies,” he wrote this March. “They fast-forward historical processes.” Even so, these works of Arthur are more than a cry of alarm.

I do not see them as joyless pessimism; rather, they are a championing of complexity, and a heartening consolation that somewhere in the madness, there is always a story in need of being told.

“That is the nature of emergencies, they fast-forward historical processes”

“Blót is one of the most materially dense of the works in the show. The composition has been built up, layer upon layer, reconciling the ‘literal truth’ of photographic sources with the subjective abstraction of painting and monoprinting. The title derives from a Neo-pagan ritual sacrifice we witnessed in the bleak, snowy landscape of central Sweden.”

End.

About Arthur Laidlaw

b. 1990 United Kingdom. Based in Berlin

Arthur Laidlaw completed his BA in History of Art at the University of Oxford in 2013, and his MA in Fine Art at City & Guilds of London Art School in 2015

Arthur Laidlaw investigates the way in which cultural dialogue is etched into architecture and places across history, to the present status of Europe today. Laidlaw, a British artist, left London for Berlin in a attempt to unpick this narrative. In 2016 he was awarded the young artist award by the Oxford Art Society, his works are collected internationally by private collectors. He has exhibited internationally over the past decade in London, Oxford, Berlin and Leipzig.